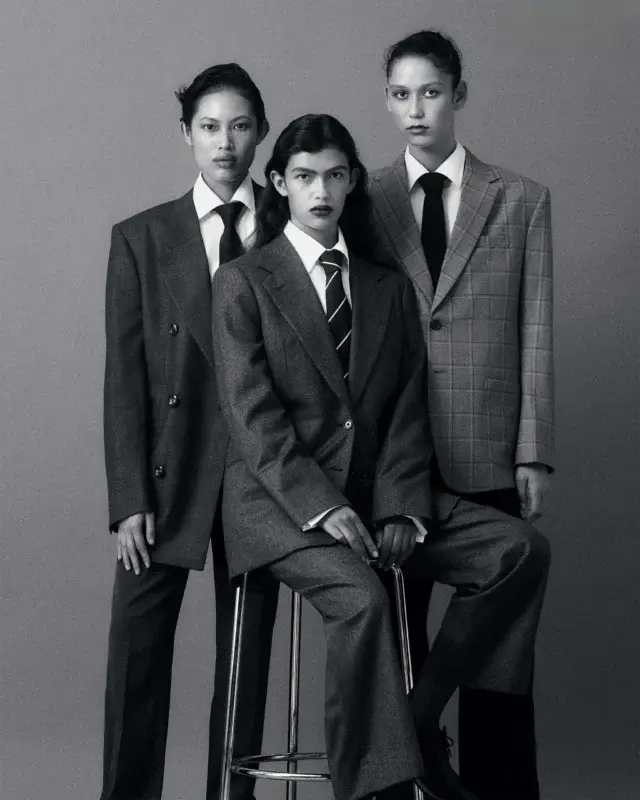

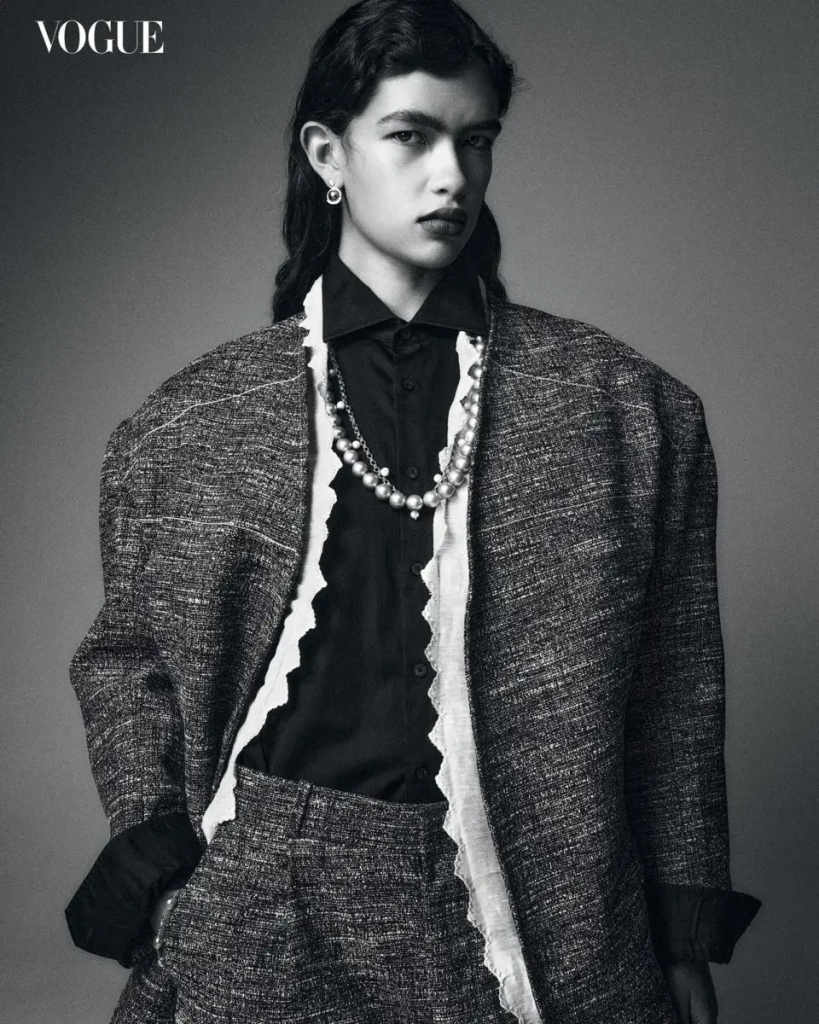

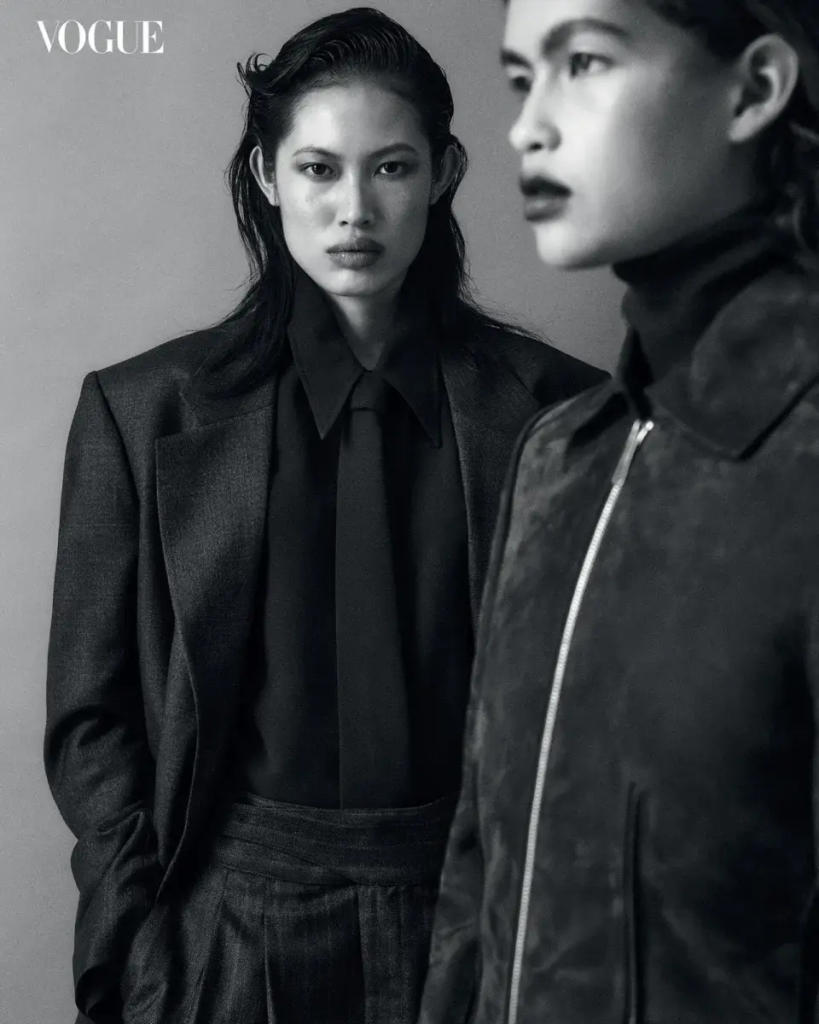

Creative director Paulina Paige Ortega explores the suit and its visual history of self-fashioning as reclamation both here and abroad.

It was a childhood memory that Paulina Paige Ortega recalled often: the sight of her grandfather dressed for a formal occasion in freshly pressed, natty layers. It was the typical formula: a coat, trousers, and a tie. As sharp as he was, it was memorable, she says, because of the particular way he referred to himself: naka-amerikána. “I just thought it was really curious,” she furthers, “that Filipinos called suits, Western suits, amerikana.”

In itself, the term held an interesting tension; for Filipinos, to wear a suit was to interact with its history: in local context, as it has evolved under Spanish and American occupation, and further within a much larger, global conversation, on the attire as a symbol of poise or power or both, of fantasy and possibility, of assimilation versus self-expression.

In the Philippines, the suit arrived with the Americans at the turn of the century. It wasn’t the first time Filipinos wore Western clothing, as seen among the ilustrado and the upper class in the 19th century, but the “suit” by modern definitions was first seen on students and young men around 1910 to the 1920s. They wore a version that suited the weather; the amerikana cerrada featured black or white lightweight drill suits, with shirts that buttoned all the way up to standing collars, and was often accessorized with a Panama hat and a walking cane.

At the time, women still wore the baro’t saya, but even then, it began to transition in favor of Western-style clothing. Historian and academic Gerard Lico narrated these shifts in Siglo 20, a compendium of 20th-century Filipino style and design, writing, “The terno stripped down the pañuelo and tapis, and fused the camisa and saya into one piece, gradually changing the silhouette from the Maria Clara to the Gibson Girl.”

“It’s the same elements of wanting to transcend any hardship by just feeling good and confident…and you know, sometimes, that’s all a person has.”

However, the terno had longer staying power over men’s Barong Tagalog and camisas. Men frequently wore amerikana, as, before the country’s proclamation as an independent Republic, Filipino elite “tried to show they were equal to the West,” wrote Mina Roces in The Politics of Dress in Asia and the Americas. By 1929, it was driven into popular culture, when writer Romualdo Ramos and cartoonist Tony Velasquez would debut the first serialized comic strip in the country within the pages of the prominent Tagalog weekly Liwayway. His titular character Kenkoy, despite his uniquely unserious, cheeky disposition, was always depicted as quite dapper.

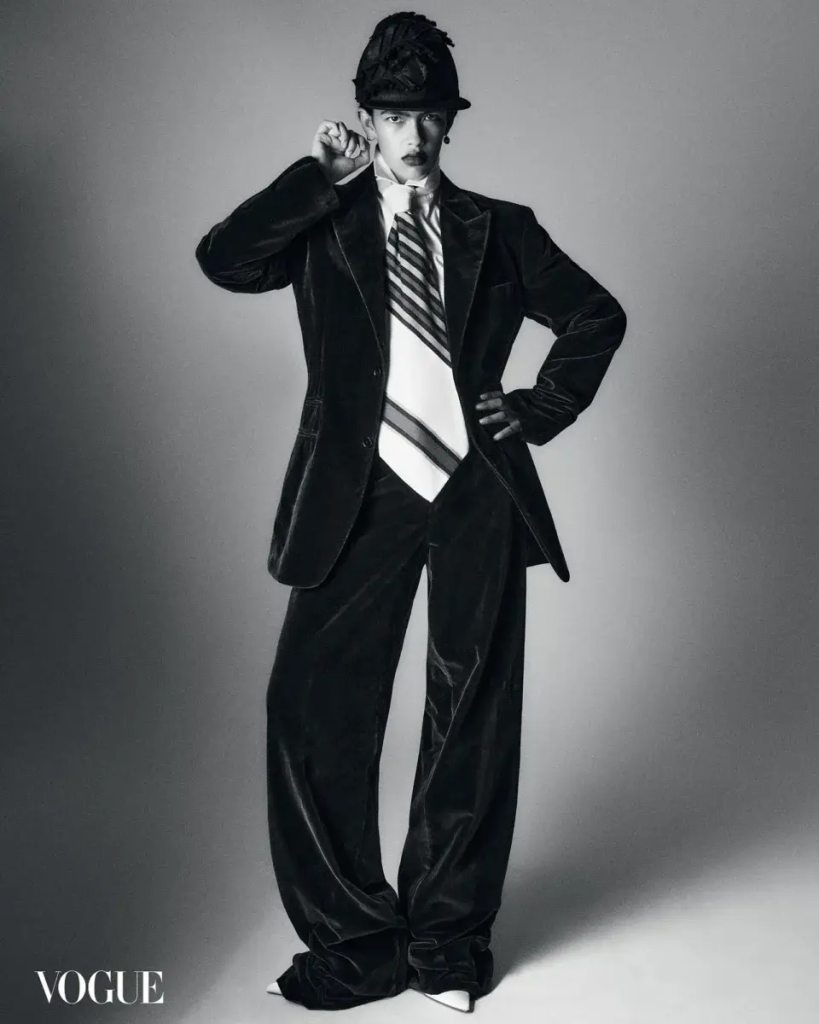

He wore a suit of slightly exaggerated proportions: a broad-shouldered coat with a cinched waist, an untucked collared shirt, and pegged trousers. On a few panels, his slicked back hair was topped with a fedora, and on others, he carried a walking cane. Intentionally or not, his appearance mirrored the look of the growing attitudes happening overseas at the same time in the mid-1930s, in America, on the far ends of each coast.

85x.com: Segurança, Rapidez e Entretenimento de Alto Nível