Not only was the suit a display of cultural identity but also a means of dandyism, the philosophical idea that first emerged in 19th-century Europe, in which “taste” is favored over all other societal means of measuring a man’s worth. In American Black dandyism specifically, the gesture of customizing drapes to ultra-specificity was later streamlined into a language of superfine: jewel-toned color-blocked suit sets, bedazzled boutonniers, fantastically patterned shirts, and neat, crisp cuts that could only be tailored-for-you. That, or whatever fit, fabric, or embellishment it takes to be “well-suited.”

“Whatever makes a Black dandy today is what made a Black dandy of the zoot suit times,” Esguerra says. “It’s the same elements of wanting to transcend any hardship by just feeling good and confident…and you know, sometimes, that’s all a person has.”

While the zoot suit fell out of fashion by the mid-1940s, its narrative for people of color in America remains and continues to evolve by the decade. Black, Mexican, and Filipino American men, as well as Japanese Americans, Jews, and other minority groups, played a role in influencing the suit that would define men’s tailoring in America to this day, set apart from British and Italian suits by its looser, freer cut, and remembered as a symbol of found community and joy. As playwright Jeremy O’Harris recently opined in Vogue, “To be a Black dandy is to dress as though you know you’re loved and therefore have no use for shame. Shame comes from fear, and fear is the enemy of style.”

By 1946 in the Philippines, amerikana remained as the only accepted dress for men’s formalwear. But attitudes began to shift in the ’50s, as the country gained independence from the United States, and as politicians began adopting a public-facing affinity for the Barong Tagalog for special occasions to win over the masses and appeal to their desire for “simplicity,” as Roces writes. Ramon Magsaysay popularly chose piña and jusi over a coat and tie, and this “deliberately distinguished the new president from the elites with Western tastes.” And by the ’90s, the needle had shifted so that the Barong Tagalog had become both a standard for formal occasions and the popular choice among grooms on their wedding day.

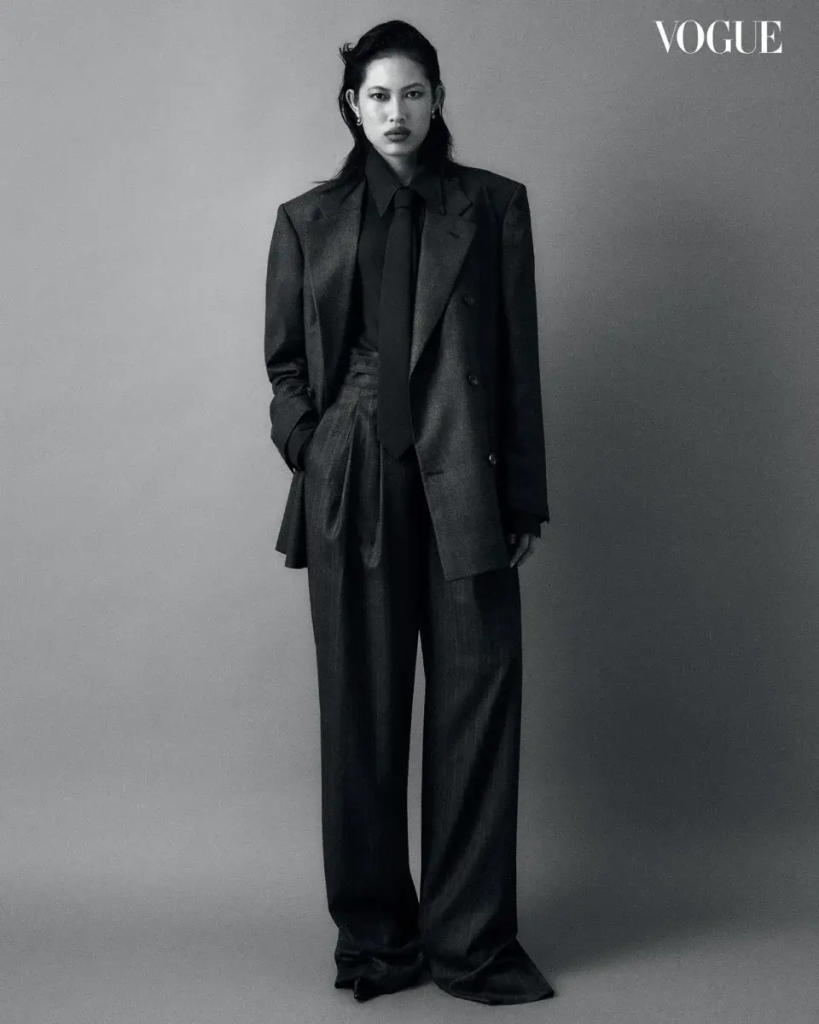

As these shifts occurred, different movements were happening in womenswear in the West, more prevalently in Italy and America. Power dressing became normalized in the workplace, with archetypal big-shouldered coats often paired with skirts, and sometimes, trousers. A coveted Calvin Klein suit might be described as precisely tailored, with broad, straight shoulders, nipped-in waists, and long lines; this was the uniform of the empowered woman who worked outside of home and provided for herself.

To wear a suit today is to carry these separate histories, of identity, empowerment, and so much else at once. Revisiting that memory of her grandfather in what he called his amerikana, Paulina Paige Ortega engages with questions she’s had since she first learned the term. How do we reclaim or engage with the suit or amerikana as Filipinos?

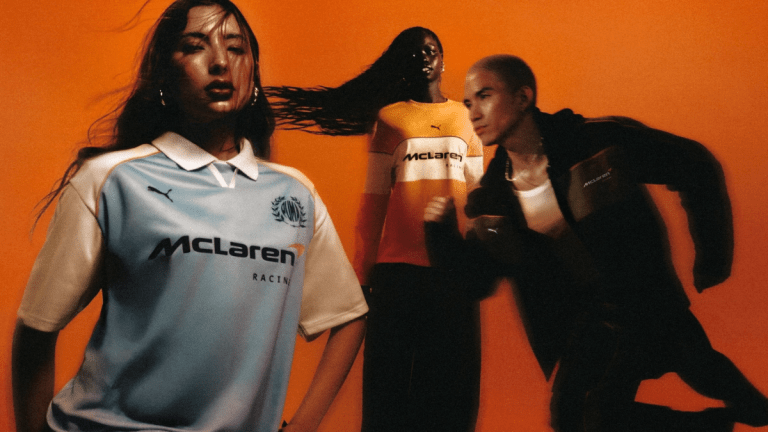

Photographed by Diego Lorenzo Jose and styled by Ilkin Kurt, Ortega’s interrogation into the topic unfolds over a mix of textures, blown-up proportions, and familiar silhouettes: in layered, sheer skirts that echo the tapis, the impression of a Maria Clara bell sleeve, and the raised collars that recall the time the amerikana cerrada arrived on our shores. She expands, “I really wanted to think about, as a Filipino in 2025, [the question of] how can I engage with suiting where I can bring other facets of my identity into it?”

“If anything,” Ortega clarifies, “this story is just a thought prompt, or the start of a conversation. I’m sure other people would have started it as well, but it’s something that we should continue having.” Wrought and wound with so much rich detail, the history of Filipinos’ perception of a suit, of the amerikana, is yet to be compiled; until then, new narratives will continue to be written. The needle still shifts.

“This conversation will evolve over time,” says Ortega. “As identity does.”

8xpg.com: A Plataforma Moderna, Segura e Completa Para Jogar Cassino Online no Brasil